Watershed moment

Alumnus Jude Samulski leaves his mark on medicine.

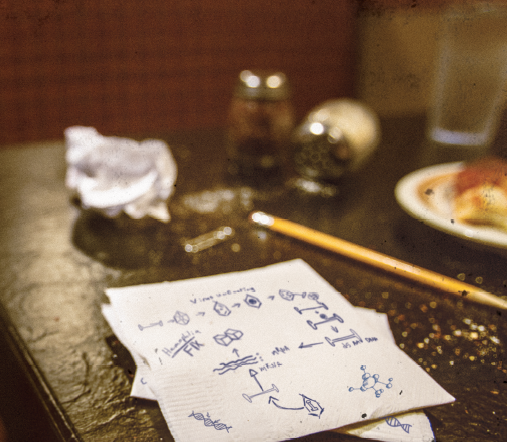

Every Friday night in the early 1980s, four enterprising scientists slid across Pizza Hut’s red, vinyl booths, ordered pizzas and a pitcher of beer — and imagined the future of science.

“There was the gang of four. Myself, Tom Pinkerton, Terry Van Dyke and Arun Srivastava owned Pizza Hut on Friday nights around 11 to 1 a.m. In that setting, we ended up discussing science forever,” said Richard “Jude” Samulski, PhD ’82. “Thirty years later, we don’t eat pizza as much, but we still sit and have those conversations.”

Those conversations led to Samulski becoming the first researcher to clone AAV, or adeno-associated virus, a virus used extensively in gene therapy. He also demonstrated the first use of AAV as a vector, which resulted in the first U.S. patent involving non-AAV genes inserted into AAV. Throughout his 30-year career, he has continued collaborating with his UF counterparts and has directed the University of North Carolina Gene Therapy Center in Chapel Hill for more than eight years.

In the late 1970s, however, Samulski was a graduate student working toward his doctorate in the molecular biology lab of Nicholas Muzyczka, PhD, an eminent scholar in the department of molecular genetics and microbiology in the UF College of Medicine. He collaborated with Srivastava, then a postdoctoral researcher for Kenneth Berns, MD, PhD, former director of the UF Genetics Institute and former dean of the UF College of Medicine. Srivastava, PhD, is now chief of the division of cellular and molecular therapy at UF and a pediatric researcher in the UF College of Medicine.

Van Dyke, PhD ’81, was a UF graduate student in medical sciences. She later married Samulski and is currently a senior investigator at the Center for Cancer Research at the National Institutes of Health. Pinkerton, now deceased, was a 67-year-old postdoctoral researcher who had a “phenomenal influence” on Samulski.

Between their Friday night pizza breaks, Samulski and Srivastava were the first young scientists to successfully clone and sequence, respectively, AAV. Now, more than 30 years later, the cutting-edge research has led to techniques that may “revolutionize the way we do medicine,” Muzyczka said.

Not your average student

Samulski was one of nine siblings born in North Augusta, South Carolina. While his seven brothers and his sister excelled in college, he struggled during his undergraduate years at Clemson University.

However, he discovered a passion for microbiology and, in turn, the study of viruses.

“I fell in love with the world under the microscope. It was like finding universes in some ways, and that intrigued me immensely,” Samulski said. “It was like ‘Star Trek’ — where no one has gone before. That was our ‘Star Trek’ — the world of viruses.”

After struggling through his bachelor’s degree in microbiology, Samulski became a lab technician for Sherman Weissman, MD, at Yale University. Weissman encouraged Samulski to go to graduate school and chase his own ideas. News about Samulski’s laboratory skills already had spread to UF, so Samulski came south to interview for a spot in the UF graduate program.

With a strong letter of recommendation from a Yale legend, Samulski found a place in Muzyczka’s lab.

A watershed moment

Samulski and Muzyczka first focused on SV40, or Simian virus 40, for human gene therapy. Berns’ lab, down the hall from Muzyczka’s, which included then-postdoctoral Srivastava, was working to develop uses for AAV.

“AAV seemed to go in and stay around for a very long period of time, which you wanted, and it also caused absolutely no disease,” Muzyczka said. “If the original virus doesn’t cause any disease, probably anything you do to it isn’t going to make a problem. That was the thinking, and it’s essentially turned out to be true 30 years later.”

In the early 1980s, Samulski was nearing the end of his doctoral studies and was determined to solve problems SV40 presented.

“Nick (Muzyczka) had the foresight to say SV40 will never be a good viral delivery system,” Samulski said. “I had to stop my project, which is the kiss of death when you want to finish at a certain time. I felt like, ‘This is my baby; I can’t give this up.’”

But at the urging of his fiancée to not delay completing his doctorate, he did give it up. And with Muzyczka’s suggestion to switch viruses, Samulski’s illustrious career of discovering how best to use AAV to deliver therapeutic genes had begun.

Today, the AAV vector is a primary tool used in gene therapy. Berns, who brought the research to UF in the 1970s, said the vector is being used to treat single-gene diseases such as hemophilia, muscular dystrophy, Pompe disease and certain diseases of the eye and bone marrow. Samulski’s lab has produced an FDA- approved AAV clinical vector used to treat children with neurological disorders such as Canavan disease and Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Samulski holds more than 20 patents filed or issued in relation to AAV vectors and has founded numerous biotechnology companies.

“The stuff we did in Florida launched the entire success of the community in gene therapy. It was a watershed moment,” Samulski said. “Only one person can step on the moon for the first time. Only one person can climb Mount Everest. Nick (Muzyczka)’s lab was the one that did it for the first time and being a part of that was exhilarating. It was like discovering gold in California; we found something we knew would be important for the rest of our lives.”